From physique to intellect... and back again?

How the AI revolution might change societal selective pressures to favour natural beauty as the next prized characteristic.

TLDR; AI will commodify and devalue intelligence, leading to natural beauty becoming the next highly prized characteristic in Humans.

Physical health as primary desideratum

From a psycho-evolutionary perspective, many human behaviours can be understood as rooted in mating strategies. At their core, these involve signalling one’s genetic fitness to potential partners. In humans, this often manifests as displays of youthful beauty in women (as a proxy for fertility) and status in men (as a proxy for resource acquisition and protection). These sexual dimorphisms arise primarily from the biological asymmetry in parental investment between the sexes.

On top of these individual selective processes, there are also societal or group-level selective pressures, including accidental ones. For instance, the black plague that killed one in three Europeans in the 14th century exerted selective pressure on immune genes, notably increasing the frequency of protective allele variants (Klunk et al., 2022).

Importantly, at a population-level, pre-modern societies preferentially selected for physical characteristics like strength and health over intellectual ones. For hunter-gatherer men, strength and endurance were the best predictors of family provisioning and protection. Likewise, for the common farmer of the Feudal era, it didn’t matter whether you were smart or not; what mattered was whether you could labour and toil efficiently and survive the harsh conditions.

The rise of intelligence

With the Industrial Revolution, and overall advances in medicine, nutrition, and sanitation, life expectancy increased, and the population grew (e.g., the population of Britain increased five times in 150 years). Societies became more literate, relying on bureaucracies, trade and technologies, and increasingly meritocratic. This resulted in a shift in selective pressures: intelligence became a prime desirable trait. Due to these multiple converging factors (notably education, nutrition, and health), average IQ scores increased over the 20th century by about 3 points per decade (the so-called Flynn effect).

Today, IQ is one of the strongest single predictors of positive outcomes, including academic achievement, job performance, socioeconomic mobility, health, emotional stability, happiness, and even longevity (Lo, 2017). As such, being (perceived as) smart confers advantages in modern societies surpassing those of physical fitness.

Interestingly, the recent decades of data seem to provide some evidence for a possible stagnation or even reversal of the Flynn trend1, suggesting we may be approaching a plateau… or a regime shift.

The devaluation of intelligence

Just as the agricultural revolution transformed society by lowering the need for less efficient food production methods, and just as the industrial revolution changed society by lowering the need for manual labour, the AI revolution is changing society by lowering the need for Human intelligence. If AI commodifies smartness, the competitive edge of human intelligence becomes diluted, relaxing related selective pressures. Once intelligence is cheaply available, the benefits of being smarter shrink, triggering a decrease in its value as a desirable status-marker trait.

In the near future, intelligence might no longer the main characteristic prized by society, providing positive outcomes and status. This raises the question: what comes next? What feature will serve as ground for future Humans to compete on?

Natural beauty and the emergence of a kalokagathos class

In a world where technology equalises for advantages related to cognitive and physical abilities and health, the new frontier of human competition may be aesthetic and embodied: beauty.

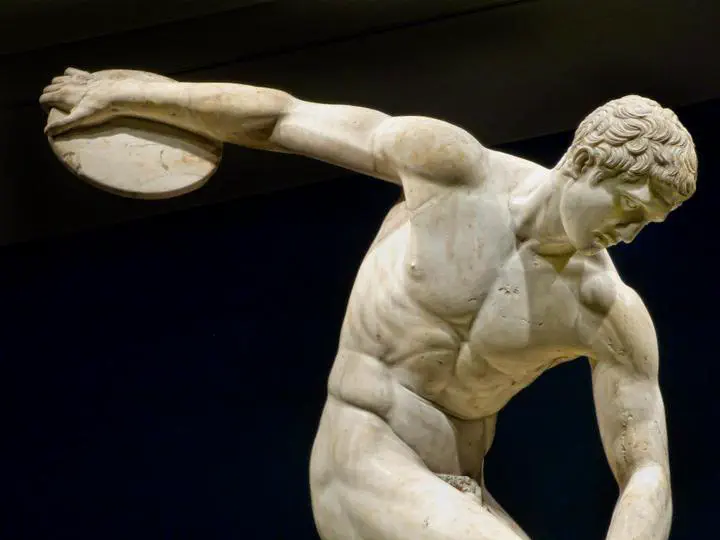

The ancient Greeks encapsulated this ideal in the term kalokagathos - the unity of the good, the true, and the beautiful within a single person. For them, beauty was not a shallow and vain superficial quality; it symbolised harmony, virtue, and authenticity.

As artificial intelligence, virtual realities, and algorithmic filters dominate experience, society may increasingly valorise naturalness - what appears genuine, unmediated, and unfiltered. The value of naturalness, authenticity, and directness2 might come as a counter-movement to the rise of artificiality, syntheticity, and virtuality. In this context, the pendulum could swing towards an aesthetic moralism: beauty as truth and goodness. In this world, natural beauty might become the prime desirable trait, with all its paradoxical implications in the form of a post-AI society obsessed with fake naturalness - surgical enhancements and digital manipulations designed to look unaltered, and carefully manufactured authenticity.

The Kalokagathoi, living embodiment of beauty and virtue, would become the new elite class, dominating not by their power to do, but through their mere quality to be, unsullied by technological augmentation. This value shift towards natural reality might last… until our technological capabilities allow us to influence the most fundamental aspects of our biology via gene editing, synthetic biology, … But what comes after that is a story for another pub theory.

1 The reversal of the Flynn effect has been documented in several developed countries, such as Norway, Finland, and the UK, with IQ declines ranging from 0.38 to 4.3 points per decade since the 1990s in some studies. However, this is not universal—gains continue in other regions—and causes are debated, including factors like changes in education quality, immigration patterns, environmental toxins, or even the rise of digital distractions like smartphones (Bratsberg & Rogeberg, 2018; Dutton et al., 2016).

2 Directness refers to the idea of unmediated experience, e.g., accessibility of the source of an experience. This translates to direct experiences of nature, social interactions without digital mediation, and raw sensory experiences. This concept also applies to products, opposing hand-crafted goods and locally sourced food (for which the “source” and “origin” are directly accessible and known) to mass-produced items for which the creation process has been obscured and mediated through complex supply chains.